Remember how I've said that understanding satire requires you to be well educated and well informed? Instead of simply reading about the history of slavery around the time when Mark Twain wrote Huckleberry Finn, I'm going to have you get your hands (and your ears) dirty by digging into the geography, art, and music of the time period.

The Geography of Slavery

To understand Huck Finn, you have to understand the geography of slavery. Take a look at the interactive map at the link below.

Use the play button to watch how the status of states changed over time.

- Huck Finn is set in Missouri (MO). Considering that the story involves a young white boy and his slave friend Jim, how do you think the setting of the novel will impact its plot?

Creating Context through Works of Art

Examine Thomas Hart Benton’s 1936 mural, “A Social History of the State of Missouri,” for scenes that tell the story of Missouri’s state history.

- What details about life in Missouri are revealed through these murals?

- What do the murals tell you about the social expectations for blacks and whites during this time?

Spirituals and Slave Songs

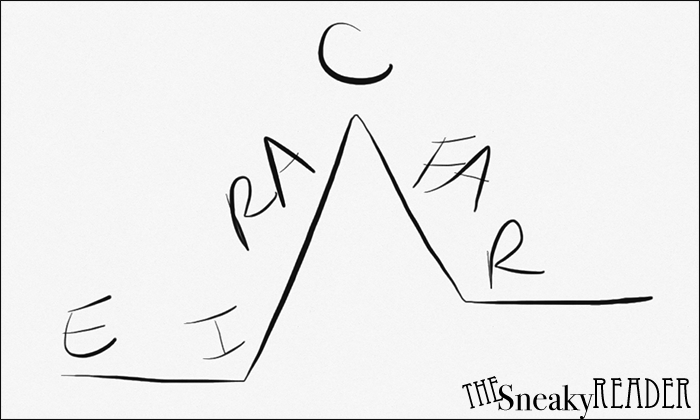

Each of these songs gives some insight into the lives, treatment, and hopes of slaves. While “Follow the Drinking Gourd” refers to gourds used for drinking water in the fields, it also refers to the Big Dipper and gives directions for escape and finding one’s way across the Ohio River to Free states. Other songs, though called spirituals, refer not only to achieving freedom through faith and death, but dually though running away. Listen to the following songs:

- What is the tone of each song and how is it created?

- What does each song reveal about the lives, treatment, and hopes of slaves?

- What importance did the river have to slaves?

Minstrel Songs

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used by performers to represent a black person. In 1848, blackface minstrel shows were an American national art of the time, translating formal art such as opera into popular terms for a general audience. Frederick Douglass generally abhorred blackface and was one of the first people to write against the institution of blackface minstrelsy, condemning it as racist in nature, with inauthentic, northern, white origins. Douglass did, however, maintain: "It is something to be gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience."

- Listen to “Dixie”

- Listen to “Old Folks at Home”

- Many of these songs are still sung today and are official state anthems. Should this be allowed?

- Do you think minstrel songs did more to help or hurt the cause of African Americans?

Abolition Songs

Abolition songs, often high-brow and quite involved poetically and musically, seek to inspire Abolitionist zeal and pity for those in slavery and should remind you of the laws governing both slaves and those who helped to free them.

- Listen to “John Brown’s Body”

- Read about the history behind the song

- What is the tone of these songs and how is it created?

- How do these songs compare to the slave spirituals you listened to earlier in terms of their purpose, goals, and ways of creating hope?